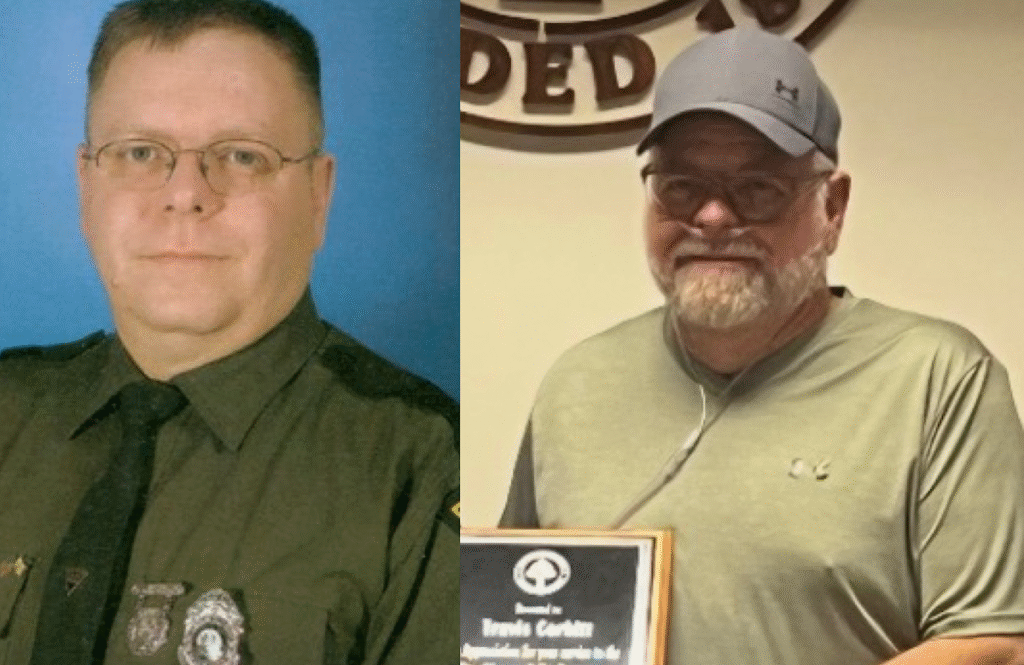

Travis Corbitt knew he wasn’t in the best shape, but he didn’t understand why he felt like he could never catch his breath. He had been a police officer for more than 40 years, but chasing down suspects and responding to emergencies was getting harder and harder.

His doctor said he might have allergies or exercise-induced asthma. Corbitt wasn’t aware of any allergies, so that “didn’t really make sense,” he said. Inhalers didn’t help. Not knowing what was wrong became frustrating.

“I don’t know how to describe it, but until you are struggling for every breath you draw, you don’t know what that feels like,” Corbitt said. “It was just a constant struggle to draw a deep breath.”

Corbitt began using supplemental oxygen. Eventually, he needed it full-time. That prompted him to retire from the sheriff’s department after 44 years on the force. Soon, day-to-day life became difficult. He came up with elaborate ways to ensure he could golf without losing his breath, and pulled his tank behind him as he walked his West Virginia property. Soon, climbing just a short flight of stairs left him needing rest.

Finally, Corbitt made an appointment with a pulmonologist.

After just a few seconds of listening to his chest, the pulmonologist diagnosed Corbitt with a condition called pulmonary fibrosis. That worried him enough. Then he was told the condition could only be treated with a double lung transplant.

“It was unsettling,” Corbitt, now 63, said. “But I’ve never been a curl up in a fetal position and cry kind of guy. So when the doc said I needed a double lung transplant, I said, ‘If that’s where we’re going, let’s head that way.'”

What is pulmonary fibrosis?

Pulmonary fibrosis is a progressive disease where lung tissue becomes damaged and scarred. The more scarring occurs, the harder it is for a patient to breathe. Corbitt’s pulmonary fibrosis was idiopathic, which means it has no known cause. Dr. Rachel Powers, a pulmonologist at Cleveland Clinic who treated Corbitt, said that IPF is a “very difficult diagnosis to get.”

“Some of the symptoms of it can be somewhat insidious, in that people just notice they’re short of breath or they can’t do quite as much, and in a lot of people, it coincides with this age range of later 50s to early 60s. That sometimes is accounted for as ‘I’m just getting older,'” Powers said. “You can kind of go through a Rolodex of seeing different physicians.”

As Corbitt learned more about IPF, he realized he had likely been coping with it for years.

“There were times where I thought I was just, you know, out of shape or whatever, when I would have to do physical exertion — chase somebody, run somewhere. I thought I was just getting out of shape,” Corbitt said. “Looking back on it now, that’s probably not what it was.”

“I have always known that death was a possibility”

Patients who are diagnosed in the early stages of pulmonary fibrosis are treated with medications meant to slow the progression of the disease, said Dr. Aman Pande, a Cleveland Clinic pulmonologist who was not involved in Corbitt’s care. In later stages of the disease, the only option is a lung transplant.

Corbitt was sent to the Cleveland Clinic to start the screening process. He had his initial intake appointment with Powers in September 2024. In May 2025, he was put on the transplant list. Because of his condition, he was placed high on the list, Powers said.

Luckily, new lungs came in “fairly quickly,” Powers said. After just a few weeks of waiting, Corbitt got the call that the Cleveland Clinic had organs for him. He and his family hurried to the hospital. The operation would be major, but Corbitt found himself at peace.

“Being a police officer for 44 years, I have always known that death was a possibility for me,” Corbitt said. “Going into surgery, I realized it was a possibility, but I didn’t feel like that was where we were. It wasn’t a huge concern for me. I realized it was possible, but I wasn’t really worried about that part of it.”

Powers said Corbitt’s surgery went “wonderfully.” The smooth procedure was followed by a “really good recovery,” she said. Corbitt said he started weaning off the oxygen four days after his operation.

“I remember one evening, I was laying in the hospital bed, and I drew a deep, deep breath,” Corbitt said. “It may have been the first one for a year. But just a deep breath. And I thought ‘Wow, that feels weird.'”

“You can’t hold me down”

Corbitt was released from the hospital three weeks after the operation, which Powers said is standard for double lung transplant patients. He then went to an inpatient rehabilitation facility to regain his strength. After another few weeks, he was back home and feeling better than he had in years.

Corbitt will see Powers regularly for pulmonary function testing, X-ray imaging and other tests to ensure his health is stable and his new lungs are healthy. Lung transplant patients see their doctors often in the year after the surgery, when the risk of organ rejection is the highest, Powers said.

In the months since the operation, Corbitt has focused on regaining his strength. In December, he welcomed his seventh grandchild. He’s thinking about picking up a part-time job at the sheriff’s department, and is excited to return to his favorite hobby.

“When it warms back up, I’m back on the golf course,” Corbitt said. “You can’t hold me down.”

Steel business owner on Trump’s tariffs as world awaits Supreme Court decision

Ilia Malinin reflects on Olympic journey and future plans

The Girl From Wahoo | Post Mortem